The Science of Tasting

The 5 (7) Senses

So hopefully we can all agree that we have 5 Senses - I won't get into the

wider discussion regarding the 6th and 7th senses.

I'm not talking about ESP but about the Vestibular sense and Proprioception.

If you wish to find out more about these then I highly recommend google – As they have very little impact on tasting I'm not going to do all the work for you.

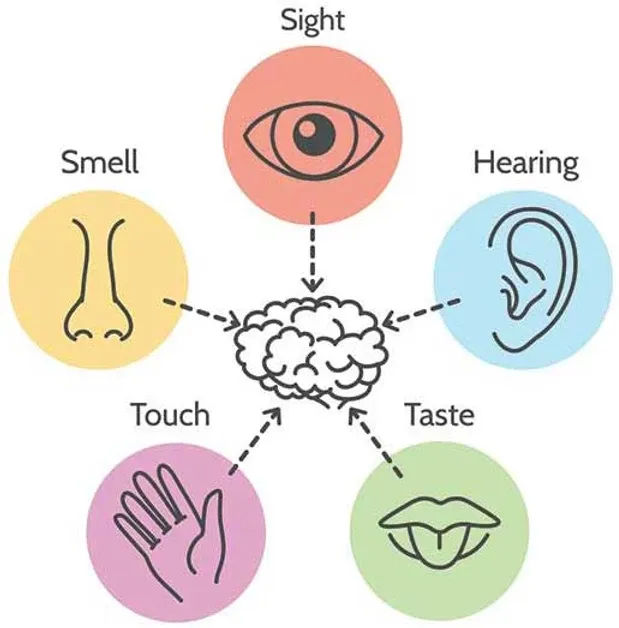

So how do these 5 Senses affect our relationship with wine?

Within these 5 Senses we have some that are Dominant and some that are Passive, Primary and Secondary or Active and Inactive - call them what you wish.

Of the 5 Senses the Dominant sense is Sight - normally I would ask people during a tasting which one is the most dominant sense and the responses I get range through all five - everyone has a different opinion over which sense overpowers the others.

As you can see from above, I've already given away the answer but let’s give you a quick explanation.

Of the 5 Senses two are active and three are inactive - Sight and Hearing are always on, they don't need an action to make them work, unless of course you walk around with your fingers in your ears and your eyes closed, but I'll ignore the idea that this is how you spend your days.

The other three; Touch, Smell and Taste need to be activated to make them work. We need to breathe in to activate Smell, we need to place something in our mouth to activate Taste and we need to physically touch something to activate Touch.

So, between the two Active senses; Sight and Hearing which is more dominant?

I've already told you this but I'm more used to talking in front of a group than writing in front of a keyboard and I like to get some audience participation going, which is much harder when writing.

Sight

Sight is dominant and when discussing the relationship to tasting there are a number of reasons for this.

Normally when tasting we have a visual representation of what we are tasting in front of us.

If you eat an apple you physically have a representation of what you’re are eating in front of you, this allows your brain to identify what you are going to eat and you will make assumptions based on this visual image.

This makes the assumption you have eaten an apple before, therefore know what to expect - we will come back to how we develop our flavour profiles later on.

The difficulty in identifying aromas when wine tasting comes from the lack of a visual representation, instead of an apple you have a glass of liquid (ignore the glass - we'll come back to this when talking about Touch).

Because we do not have a visual representation of what we are going to taste it makes it much harder to be able to identify the flavours present in a wine.

Your brain is not making the association to the flavour in the liquid and your memory of previously tasting those flavours, which would allow you to pick out the individual characters found in the wine.

When tasting an apple of course you can taste the apple, but without the visual stimulus in front of you it is much harder to identify that it is the flavour of an apple that you are tasting.

You need to convince your brain you can taste apple without the actual apple in front of you.

This is why some people when faced with a glass of wine will say it tastes like wine, whereas the next person will start to wax lyrical about the wine, describing a plethora of fruits, floral notes and maturation characteristics.

The person who describes it as tasting like wine hasn't trained themselves to be able to identify flavours without the visual stimulus, the slightly more verbose description comes from someone who has.

"It deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe."

So just like your brain can interpret the words above we need to try to trick the brain into tasting something that we can't actually see.

Luckily this is not that hard to do with a little patience and time.

There are many ways to train yourself to be able to identify these flavours and we will discuss these in more detail later on.

See how I subtly attempt to make you read the whole post.

For which you will need patience and time. I obviously have a tendency to waffle.

Colour

Another way that sight impacts upon tasting is our interaction with and our assessment of colour. The wine is colourful and colour plays a large impact on how our sense of sight perceives things, the more colourful the food the more flavourful we expect it to be.

A ripe strawberry is bright red and you, therefore, expect it to be juicy, sweet and bursting with berry goodness, same goes for a fig, the deeper the colour the more powerful the flavour expectation.

Colourless food is generally going to be less flavourful, think boiled potatoes, plain pasta, egg whites, these are generally foods that have little flavour.

There are obviously exceptions to every rule and cheese is the easiest one - though even within the exception colourful cheese is generally more flavourful than colourless cheese - Stilton vs Mozzarella.

So, there is an automatic association between colour and flavour.

This has been known by the soft drinks industry for a long time, think of sodas, most of them are brightly coloured, this is done because, if a drink is brightly coloured when we taste it, we think it is sweeter than it actually is.

By adding colour to lemonade and making it red the manufacturers can add less sugar as our perception will be that it is actually sweeter than it really is.

This is one of the reasons when we are wine tasting, we don't focus too much on what we see.

If you spend too much time thinking about what the wine looks like then you will start to make assumptions about how the wine is going to taste.

If a wine has a delicate light ruby colour (if you haven't seen the WSET SAT or Systematic Approach to Tasting, then I highly recommend looking it up), then you will start to make guesses about how the wine will taste.

If you have tried wines of a similar colour before then you might guess it is a Pinot Noir or Gamay - you will then start to remember all the wines you've had before and you will then make the association between what you have tasted before and what you can see in front of you.

Sadly, because Sight is the dominant sense your brain will take this information as fact and you will actually start to taste the things that you expect to taste.

Therefore, when we are tasting wine, we try only to look at the colour, the intensity of the colour and to make sure the wine is clear, not hazy.

When teaching the WSET we also tend to do this fairly quickly so we focus less on the appearance and more on the aroma and taste of the wine.

Another example of our eyes affecting the way we experience things can be seen when we look at the McGurk Effect

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2k8fHR9jKVM

Go on. I'll wait. It's actually fascinating so I highly recommend watching it.

No?

Ok then, no worries.

Well, the McGurk effect shows how our eyes can distort what we actually hear.

Our sense of sight is so powerful it can override what we actually hear because hearing is the second dominant sense you can hopefully understand how sight would also be able to override what we taste as well.

Now there are other things that will affect how we perceive things.

I will not go into the worst of these which for me is blindness, something I can't even comprehend being able to deal with.

There is a condition called Synaesthesia which is only experienced by around 1 in 2000 people.

It is a joining or merging of the senses that wouldn’t normally be connected. The stimulation or activation of one sense causes an involuntary reaction with another sense.

The word literally means joined perception.

This means that someone with Synaesthesia could see words in colour or tastes in shapes, they will make an association meaning that they may see a particular number in green or a particular word as a triangle.

So, if I said the word nine, they would see it in their mind's eye as nine.

Now to make this even more confusing not everyone with synaesthesia will see something in the same way, so one person will see the word nine as green and the next person might see it as red.

It is thought this is linked to a cross-wiring, so to speak, in the brain where two different sensory systems are joined together instead of separate.

Colour and hearing are the most common and this is of particular interest as one of the biggest mysteries in science is how the brain binds multiple sensory inputs together to create an image as a whole.

Think of holding a flower, you feel its shape, texture and colour, smell its scent and your brain binds all this information together so you have the image of a flower in your mind’s eye.

Now people with Synaesthesia could have extra perceptions that add to their concept of a flower, this could help us understand how the brain binds information and how we perceive our world.

Synaesthesia isn't necessarily a bad thing as it can help with memory as there is an extra association being made in the brain, this can actually make it much easier for people to make the association between the flavours in wine without the visual stimulus.

However, because not everyone experiences it, and those who do experience it, experience it in a different way to the next, it can be quite hard when trying to describe the phenomenon to someone else.

There is another condition called Aphantasia, which I have, I will not say suffer from it as I have always been this way and therefore don't feel like I'm missing anything.

Aphantasia is a condition meaning we can't picture anything in our mind's eye. For most people when asked to visualise something, a beach, a person’s face, a gibbous moon (sorry I love the word gibbous - google away as needed) and so on, the image will pop into their heads, this can either be a blurred image or can be picture quality and clear as crystal.

For me it is just a screaming black void, not actually screaming but you get the idea.

Now, this can be difficult as our memories are often tied up with images, it does give me a great excuse when I don't recognise someone I've only met once before - not that I use it - saying sorry I have Aphantasia just to avoid a slightly awkward situation seems a bit of a cop-out. But that's just me.

Also, just to ignore what I just said above, I have a great memory, but it has always come from reading and listening and I, therefore, feel very little need for pictures and visual stimuli in textbooks.

So, when writing and creating presentations I have to make myself include images as this is not something that I personally need but I know we all learn in different ways.

When it comes to tasting this hasn’t affected me in any significant way, though the lack of a way to make a connection can be difficult as smells can trigger visual memories which help to identify flavours in wine.

Both of these conditions affect the way our brains deal with sensory input, Above, we saw that the brain binds multiple streams of sensory input together instantaneously to create an overall image of what we are experiencing.

So, when we are tasting we are relying on all of our senses and how these senses function has an impact on how we taste.

So, as we have seen sight is very important, what about the other senses?

You guessed it. Touch

Even though Touch is thought to be the first sense we develop, it is not as important as you might think in regards to tasting.

Let’s go back to the idea of eating an apple, your mind makes the connection between what it can see and what you will taste.

After you have seen the apple the first sense that will come into play is touch, you physically have to pick the apple up to be able to eat it, so the feel of the apple will be taken into consideration, if the apple is firm we expect it to be juicy, if soft then either bruised or even rotten.

If the skin is tight, we expect it to be ripe, if wrinkled then past its best and floury.

That's just the initial tactile sensation of your fingers, the sense of touch also applies inside your mouth, on your lips, even your teeth, think of all the actions of eating an apple, the first bite, the crunch, the release of juices onto your tongue, all of these sensations will affect how the apple tastes.

Think now of eating a strawberry, the soft flesh, the seeds on your tongue. Or a pear, the sugary sandy texture, the soft yet firm flesh. All of these will produce a tactile memory of how the particular fruit felt as you tasted it.

Now when we apply the sensation of touch to wine tasting we are primarily thinking of two of the things we note when tasting.

Tannins

Tannins are polyphenols found in fruit skin, seeds, leaves and wood. Polyphenols are macromolecules made from phenols which are complex bonds of Hydrogen and Oxygen (Sorry but it does say science in the title).

In wine, tannins come across as the drying and slightly bitter sensation we get when tasting wine (mainly red but as tannin also comes from wood any oaked white will have some tannin, as will any skin-contact whites).

It is most easily perceived at the front of the mouth under your lips on your gums. If you think about drinking tea, especially if it has been left to brew for too long the tannins are that mouth-drying, astringent sensation that you experience.

Tannins are found in the skins of grapes in differing quantities depending on the grape variety, so if you don't like tannins or bitterness then you will probably like low tannin reds like Pinot Noir and Gamay more than others like Cabernet Sauvignon and Nebbiolo (Barolo and Barbaresco).

Body

The other way touch will impact tasting is through the body of the wine.

The body in wine or the texture or mouthfeel comes from a mix of the elements found in wine, the acidity, alcohol, tannins and sweetness all impact the body of the wine

Body, is most easily thought of in the same way we think of milk, think how watery skimmed milk is then move through the spectrum of semi-skimmed, full fat, single cream and double cream or even yoghurt - now wine is never going to be a full-bodied as double cream but this gives you an idea of how to think of the body of the wine.

If you are anything like me you can't drink milk or cream (does anyone actually drink cream? I mean really?) then visualising the taste of skimmed milk is nigh on impossible and the thought of actually tasting them in order to know what I'm talking about is stomach curdling, to say the least.

For those like me, I always switch to the idea of juice, apple juice is going to be light-bodied, mango juice in comparison is going to be more medium and then a smoothie will be full-bodied.

If you like full-bodied wines then wines with higher levels of sugar, tannins and alcohol will be more to your taste, something like a Cabernet Sauvignon or an oak-aged White Burgundy.

Whereas if you prefer light-bodied wines anything with high acidity should hit the spot, a dry Riesling, a Sauvignon Blanc or a Pinot Grigio.

We can now hopefully agree that Touch is fairly important.

Hearing

Hearing although it is one of the dominant senses is actually not that important when it comes to tasting.

Think back to eating an apple, touch plays a part, picking up the apple and biting into it, and hearing only really comes into play with the sound of biting the apple.

This will give you the idea the apple is crisp and ripe as that crunch sound will only come from firm ripe fruit, a similar perception to the tactile feel given by the feel of the skin or again that first bite.

So apart from the noise of the interaction between the teeth and the tactile crunch of an apple, or the cracking noise of pork scratchings hearing doesn't play too many roles in the gustation (tasting) process.

In wine tasting there is the added sound of the wine, or sparkling wine being poured, that will allow us to anticipate the taste.

The other way Hearing is important when wine tasting is speech.

When tasting wine, it is best to do it with a group of people, either in a classroom setting or with a group of friends.

This way we get more people and more opinions, think back to the example of a person saying the wine tastes like wine versus the one who used multiple descriptors.

In a classroom situation this happens more than you would think, one person will be pulling out flavours left right and centre, another will sit there silently and someone else will say, I just taste wine, how are you all tasting all these things?

When we mentioned how the visual representation allows our brain to identify what it will taste we spoke of association, without the visual it is hard to make the association between what you are tasting and what flavours you can pick out in the wine.

This is where Hearing comes back into play, with multiple people tasting and talking about what they can taste it can help people to identify the flavour they have tasted but been unable to identify.

Someone shouting out ‘blackberry’ can help the next person who was struggling to identify the flavour suddenly agree with what they heard so they can then taste and identify the blackberry.

They are making the association between what they can taste and the concept of that flavour in their brain but without the previously needed visual stimulus.

The one thing that needs to be carefully monitored in this situation is if they hear someone in a position of trust and authority say what they can taste. Because Hearing is a dominant sense it can override what the student can actually taste and they will think they can taste something even when it is not there.

So, when standing in front of a group I always take pains to identify this phenomenon.

After telling them that they will generally taste what I tell them I can taste, hence the reason I make them do all the work by telling me what they can taste first. I will then, on occasion, slip in random comments such as 'dark chocolate' into a white wine or 'pear' into a full-bodied red.

This helps the students to challenge what I'm telling them as I've previously warned them of the danger rather than accepting it and tasting something, they can’t identify.

If you remember back to the McGurk effect, your eyes can trick you into hearing something different, in the same way, your hearing can trick you into tasting something that isn't there.

There are multiple experiments into how sound interacts with taste, it can give you an insight into why aeroplane food seems to taste so bad, sweetness and saltiness are blocked by loud noises. So, the constant din of the engines has an effect on how your food will taste.

There have also been experiments based on sounds being played and the effect it has on flavour.

The sounds of the seaside can make us taste fish, the sounds of the farmyard can make us taste either chicken or eggs and the sizzling sound of frying can make us taste bacon, either to a greater extent than is actually present in the food or tasting it even when there is no flavour present in the food.

Taste

Right on to Taste

We have papillae on our tongue, the little bumps you can see and feel (there are lots more you can't see or feel), these contain your taste receptors, there are 2-4 thousand taste buds on your tongue. There are more dotted around your mouth, in your nose and down your throat.

These taste buds interact with the chemicals in your food and drink and then identify the following tastes.

Just like we have 5 Senses we also have 5 Tastes; the image above shows you the names.

Sweet, Salty, Sour, Bitter, Umami.

Sadly, the image above is still being taught and used in textbooks.

I'm assuming you've heard of the Tongue Map, this is the idea that we taste sweet and salty at the front of our tongue, umami in the middle, sour on the sides and bitterness at the back (randomly this is why in beer tastings we are encouraged to swallow whereas in wine tastings we spit - beers have bitterness and it is assumed we need to swallow them to appreciate this whereas wines don't – so beer tastings are more fun).

The idea originally came from a German student's thesis which was mistranslated and became accepted as fact, even though it was disproved back in the 1970s.

We all perceive all of the 5 tastes across all of our tongues, some people will have increased sensitivity to certain tastes in certain areas but they will still be able to identify all tastes on all parts of the tongue.

There are other things we can taste such as metallic, chalky and fatty which are being considered as additional tastes to supplement the current 5.

We also have a chemical sensitivity on our tongues which allow us to 'taste' heat(spice), the prickle of CO2 and cooling (mint/menthol), these are not tastes but sensations.

Regardless (sorry for obvious reasons I refuse to write irregardless (spell check is exonerating me here, or it's telling me off)) of the tongue map we all taste the 5 Tastes.

Sweet

We are born liking sweetness, it is an in-built survival trait making sure we are predisposed to like breast milk, which has a certain sweetness for this very reason (think Friends and cantaloupe juice).

The fact we like sweetness is also linked to evolution, primates and early foragers realised that the sweeter the food the more energy they had, this can be linked to ripe fruit and honey being eaten in preference to other foods as they had more energy during their days searching for food.

Sugar also contains endorphins which are linked to happiness and beta-endorphins which are a mild-painkiller so, sugar helps us to relax and also improves our mood.

Think of early foragers being stung trying to get honey, the pleasure gained from the food overrode the danger factor.

Nowadays nurses use this predisposition by giving babies something sweet to distract them when giving them an injection. They will focus so much on the treat that they don’t notice the pain of the injection.

Salt

Salt is needed for survival, our body needs salt, without sodium in our diet we will die.

If we have a salt deficiency our bodies are programmed to cause dehydration which makes us thirsty and hungry causing us to digest food and drink to replace any missing electrolytes in our body.

Sadly, both Sugar and Salt are addictive and our bodies become tolerant to them so the more we have the more we want and we keep having to increase the dose as it were.

Acidity

Acidity causes our mouths to water, this is linked to ripeness, the riper the fruit the more balanced acidity can be found which increases the flavour perception of the food.

Acidity in wines can be detected by how much you salivate.

Think of a Sauvignon Blanc or Riesling compared to a Viognier or Torrontes both can be fantastic wines but the acidity of the former makes them feel more refreshing.

Bitter

Bitterness is again linked to evolutionary traits, in the wild bitterness was associated with food that was either unripe or poisonous.

So, we are naturally inclined to dislike bitter tastes.

Bitterness as a taste only became acceptable to our palates as it was intrinsically linked as having a benefit to us, think of medicine or stimulants.

Coffee and alcohol are bitter and unpleasant to taste at first but because they have a positive effect they are tolerated and then enjoyed. This benefit allowed us to override our natural distaste for bitterness and incorporate them into our diets.

Coffee gives us energy and keeps us awake and alcohol has other pleasant side effects that hopefully counteract the negative ones (the I'm never drinking again moment).

Umami

Umami is relatively new to the 5 Tastes, it wasn't taught when I was in school and was only added in 1990, even though it was discovered in 1910, so you now have a rough idea of how old I am.

The easiest way to describe Umami is savoury, think cooked mushrooms, soy sauce, miso soup etc.

Just like sweetness, glutamate the amino acid that gives us the Umami taste is also present in breast milk, so we are exposed to Umami from a very early age, there is no wonder that it has become an important part of our diet.

Umami is beneficial to our diet as the glutamate in Umami is not bound to other amino acids making it easier to digest meaning less energy is consumed during the digestion process.

Smell

It's all about Smell.

Well, not all but hopefully you get the extra stress I'm putting on this sense.

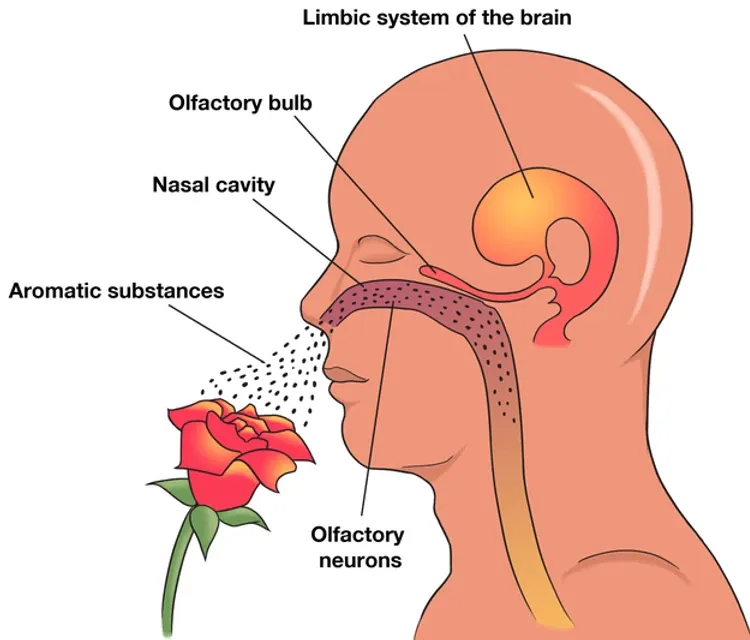

Our sense of smell comes from our Olfactory (in my head I always switch the L and F so want to pronounce it Oflactory - weird as I am) receptors and binding pockets in our nose, these identify individual aromas (this can be made up of multiple odours at the same time) and then send that information to the Olfactory bulb which identifies them.

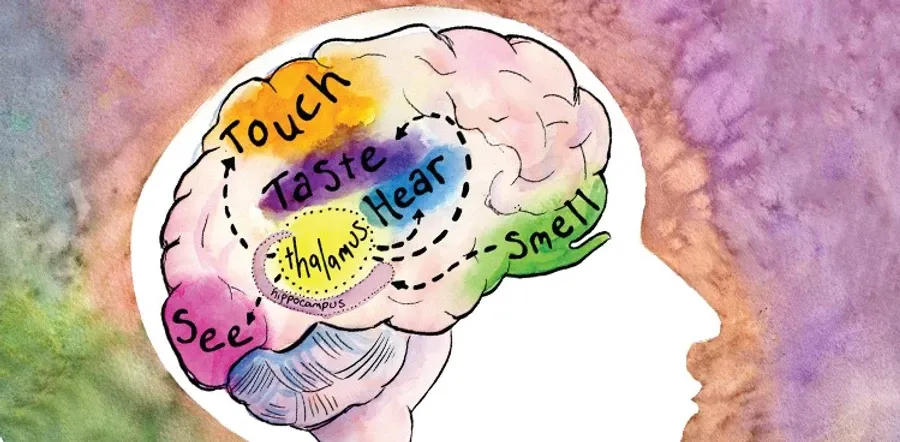

The olfactory bulb works along the same principle as facial or pattern recognition, this then sends it to the Olfactory Cortex which is linked to the Limbic system in the brain which matches odours to memory.

This is where we get our Database of Smell or Memory Bank of Aromas, it holds all the aromas we have experienced alongside both the negative and positive associations and allows us to remember having smelt something before.

Normally this comes with other stimuli from all of our other senses but it exists in our Olfactory cortex as a standalone identifier.

So hopefully in the above section, you noticed that we only spoke of 5 simple tastes - there was no mention of the flavours found in food or wine.

That's because all of the things we think of as tastes are actually aromas. Don't believe me?

Have you ever tried to eat something when you have a cold, by removing the sense of smell from the equation you can't really taste anything, the same (almost) applies if you hold your nose when eating or drinking.

You can still taste the 5 Tastes; sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami (the order changes depending on what I'm thinking about) but you can't taste any aroma.

So, strawberries will taste sweet and you will be able to identify them because of the tactile feeling in your mouth, but the fragrance of the strawberry, the aroma will be gone.

To make this experiment even more viable close your eyes or blindfold yourself, hold your nose and have someone give you different things to taste.

By removing the visual aspect, it makes it virtually impossible to identify what you are tasting, as even without your sense of smell your eyes will tell your brain what you are eating so you will expect a certain flavour.

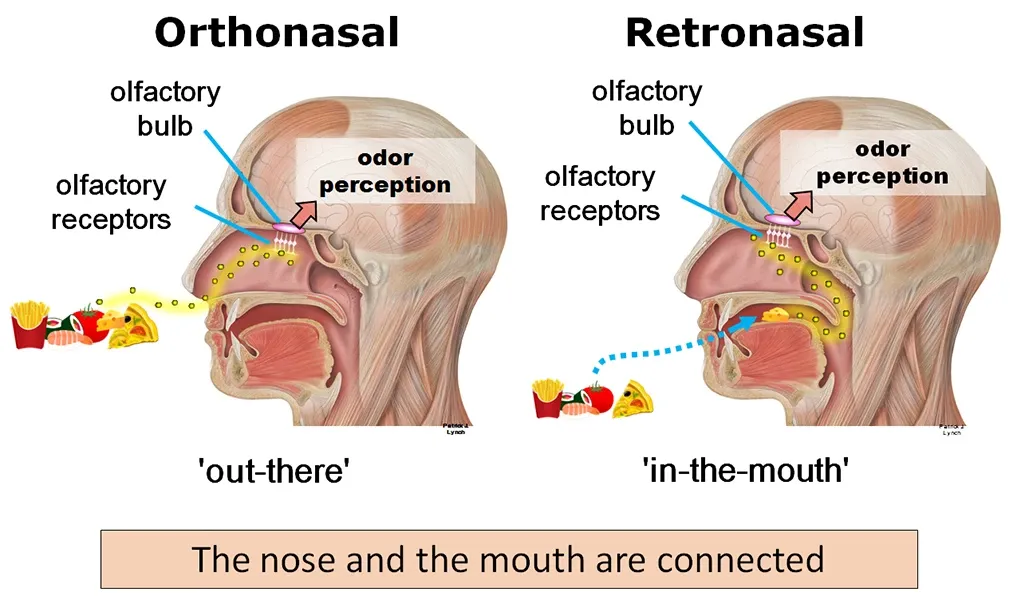

This is all because of the Retronasal passage, which links our mouth and nose.

When wine tasting we activate the retronasal passage by drawing air into our mouths over the top of the wine, this draws the aromas through the retronasal passage and into our noses increasing the intensity of the aromas.

There is no way to do this without looking fairly daft, although the sound effects many people produce are not actually necessary.

Come to a WSET tasting and you will see what I mean.

There are other factors that will dictate how much we can detect via the retronasal passage.

We have enzymes in our mouths which will interact with the chemicals to either suppress or release aromas meaning that in some cases aromas are amplified and in others, they are removed entirely.

For example, Sulphur which in wine can have the aroma of a struck match can be detected orthonasally but not retronasally.

The warmth of your mouth will also help to release aromas.

The colder something is the less you can taste it, think of an ice-cold beer, very refreshing but doesn't have a lot of flavour, by increasing the temperature we can identify more aromas.

There is sadly a reason some drinks are served as cold as possible.

When we smell we are engaging our Orthonasal receptors, by drawing air in through the nose we are bringing aroma compounds within the air into contact with our olfactory receptors, this is where our sense of smell comes from.

So, all those lovely flavours of roses, peaches, rosemary, and pine as well as the unpleasant aromas of rotten fruit, garbage and other less pleasant things I will not mention but leave you to imagine, are actually aromas, not tastes.

Everything you think you can taste is actually smell.

Also, everything you can smell you are technically tasting; your body is actually absorbing the aroma chemicals to be able to identify them.

Another unpleasant thought for you.

Now in both Taste and Smell, we have flavour thresholds; we are more susceptible to some things than others. This is why when tasting someone will instantaneously be able to identify certain notes and others can't pick them out at all. The same goes for tastes, to someone a wine will be overly sweet and to others not at all.

There are tests we can do to work out our personal thresholds, which allow us to understand how we taste in comparison to others, such as PTC chemical strips to detect bitterness.

Always a fun exercise to do in a WSET class.

The combination of our senses of Taste and Smell gives us our overall impression of flavour, so the aromas of fruit, plus the taste, the sweetness and the acidity all combine into the flavour of the fruit.

The Brain

Then the brain has to pull it all together.

The Limbic system, which is linked to our mood, memories, emotions and behaviour is also linked to smell and taste.

This is why there is a correlation between what we can smell and how we feel.

Our sense of smell will literally (not really, it’s not a time machine) take us back to the first or most important time that we associate the aroma with and we can re-live it.

Everyone will have a different reaction and perception to a smell, this is dependent on when you first experienced it and what your reaction to it was.

Smell was initially used as a way to establish attraction; it still is and can be seen in the fact the perfume industry is worth around £40 billion annually.

We all like different perfumes, if someone could find an aroma that was equally appealing to everyone, they would make a fortune, sadly due to the way we experience aroma, based on our Limbic system this just isn't possible. Not that this will stop them from trying.

Initially, Neanderthals would smell potential mates to see if they liked their smell, this is also linked to food, as pleasant-smelling food is more likely to taste nice than unpleasant ones.

The Elizabethans took this further and used what is called a 'love apple' to gain the attention of their potential suitors (again I'll let you look this up - but make sure you include Elizabethan or it'll just come up as a variety of tomato).

Sadly, there are numerous different things that affect our sense of smell. They are fairly uncommon and can be temporary but still affect millions of people around the world.

Hyposmia means you have a reduced sense of smell.

Anosmia means you can't smell anything at all. You can also be Anosmic to a certain smell, so you wouldn't be able to smell rosemary for example.

Phantosmia means you smell things that aren't actually there

Cacosmia is a form of Parosmia, which is a distortion of smell, Cacosmia means everything smells of something you identify as being disgusting.

This can obviously make it difficult to be able to taste anything, there is research showing that by regularly exposing yourself (wait for it) to certain smells you can increase your awareness of them and help to reverse Anosmia.

Our Limbic system as stated above will also remember unpleasant smells, this can cause what is known as 'bait shyness'.

The name is linked to animal trapping, when a hunter wanted to catch an animal rather than kill it, they would lace bait with poison to incapacitate the animal. This would make them sick and from that point on they would have a severe reaction to the smell or taste that they associated with the bait.

In humans we have the same response, think about someone who can't eat oysters or mussels, this is generally linked to having been exposed to a bad one and the severity of their reaction makes it physically impossible for them to try them again.

It can also be linked to food phobias in childhood as well as certain smells, if something smells rotten then we react to it as dangerous, especially if you ate the item as this links the item to a physical reaction as well.

Genetics

A lot of how we react to certain aromas and tastes can be linked to genetics.

It has been discovered by researchers at Duke University that everyone has 400 genes related to the sense of smell.

The combination of those genes gives us 900 000 variations, so if one gene has one amino acid that is different to the next person then you will experience that smell differently.

This means on a genetic level that there can be a 30% difference from person to person.

Tie this back to the Limbic system, emotional response, experiences, sensory physiology, sensory neurology and our individual memories this means that everyone will identify with different smells based on their experience.

Now for some of this, we can blame our parents based on our genetics and also our exposure to food, both as infants and in the womb.

If your mother was sick when she was pregnant with you then you will have a pre-programmed preference for salt.

If you’re regularly sick then your body craves sodium to replace the lost electrolytes that have been purged from your body, if this happens during pregnancy then the cravings will also be felt in the womb and the baby will also crave salt.

So, after the baby is born it will have a preference for salt.

What you eat when you're pregnant will also affect your child. If you spend your days eating spicy Indian food then your baby will be exposed to this as well, meaning they will have the flavour imprinted on them before they even get to try it.

This also applies to when you are breastfeeding as flavours are passed through the milk (again think of Friend's and cantaloupe juice, more insight into what Carol was eating than you expected or probably wanted).

The more variety your baby is exposed to the more they will be willing to try when they move onto solid food.

Think of it as future-proofing your baby against arguments about eating their vegetables.

Also, the more variety they are fed as children the more diverse their diet will be when they are older.

It doesn't just apply to food, babies and children will have an instant emotional response to the perfume worn by their mother when they were pregnant. This is because the perfume is absorbed by the skin and passes to the child.

So, the child will be drawn to the smell of the perfume and will seek physical contact.

When babies are born they do not have all of the 5 Tastes.

They can taste sweet from birth, as mentioned before this is linked to survival as breast milk is sweet.

But their other taste buds don’t mature until later (around 4 months old), from birth babies can’t taste salt, which can be very dangerous.

If a baby eats salt, because they can't taste it there is nothing that stops them from continuously eating it.

Babies can die if exposed to high levels of salt and their tolerances are much lower than adults.

But a baby will reject bitter foods, even though they would consume far too much salt their self-defence mechanism will kick in if they come into contact with something bitter.

For someone who crawls around on the floor and puts everything in their mouths, this is a natural defence mechanism relating back to when humans crawled around the forest floor.

It also goes some way to explain why babies won't eat certain veg, sprouts and broccoli, for example, are high in bitterness compounds.

This genetic predisposition only works on Taste, not Smell, there is no smell that can harm a baby so they do not have an aversion to aroma like they do with taste, aversion to certain smells are learnt as we grow and experience them.

There is also a phenomenon called Neophobia which many children experience, this is the irrational fear of something new, it generally manifests as an aversion to unknown or novel foods.

This is why so many children won't try certain foods.

Luckily children under the age of 2 do not experience Neophobia so it is best to expose them to as many different foods as possible, this way they will accept certain tastes and flavours and after repeated exposure, the flavours will be integrated into their diet.

All aversions to flavours and tastes can be overwritten by experience, if you eat anything 5-10 times you will eventually tolerate and even grow to like it.

Think of your 1st experience of olives, coffee and alcohol, it is rare anyone likes their 1st experience of these things, but as a non-coffee drinker, it is much rarer to come across someone who doesn't drink it. So, a vast percentage of the population have overcome their initial distaste and now have incorporated coffee into their diet and enjoy it to such a degree they struggle without it.

Supertasters

I'm sure you've all heard of Supertasters, maybe to the extent that you wish that you were one.

All a supertaster is is someone who has more papillae and therefore more taste buds making them highly sensitive to certain tastes.

This is not necessarily a good thing, if you are a supertaster that can mean you are much more susceptible to bitterness, which means you generally won't like bitter flavours as they will be too strong for you. Now imagine your life without coffee (or coffee that has to be drowned in milk), without IPAs or Olives or any of the other food and drinks high in bitterness.

Still, want to be one?

Everyone’s tastes change over time (this is called neural plasticity), it doesn't just apply to food and wine. Think back to when you were 18 or so (or even younger if you are only 18 now).

Think of the type of clothes you used to wear, how you styled your hair, the type of music you listened to.

For many people (especially those who grew up in the 80s) that may be fairly cringeworthy. Luckily, we acquire and dispose of our preferences regularly, this means that our tastes will change over time.

It doesn't mean that what you once enjoyed was bad, at the time it may have been the height of fashion, or what everyone was drinking. It just means that you have changed and at the same time society has changed so our reactions to the things we used to like are determined by our current experiences and society's reaction to it as well.

A lot of what we like depends on when we were exposed to certain stimuli.

If you think of when you were first exposed to horses, the memory could fill you with a feeling of either delight or fear.

If as a child you were exposed to horses from a young age and remember charging through the fields on a sunny day then you will most likely have a positive association.

If the first time was walking through Hyde Park and nearly being trampled because you didn't realise people rode inside London then your association will probably be fairly negative as it could be if you were charging through the fields and the horse threw you and you broke your leg.

The same can apply to your wine preferences; if you taste Sauvignon Blanc most people will agree that there is an undeniable fresh grass characteristic within the wine.

Now if you have positive memories of summertime, playing in fields with that lovely smell of cut grass then there is a fairly good chance you will like Sauvignon Blanc.

If you have negative memories such as hiding inside because of your allergies whilst everyone else played outside, or an even more extreme example could be that you could have had a psychological incident linked to losing your foot to a lawnmower accident. Then the chances are you won't like Sauvignon Blanc.

These positive and negative associations can come from childhood or can be linked to other factors.

If your doctor has said you have too much salt or sugar in your diet then the chances are you will avoid them and eventually build up a negative association with them.

Becoming a better taster

We can change how we react to certain things by positive reinforcement and associative learning or conditioning.

If you keep trying olives until you start to like them and associate them with doing something else you enjoy, eating tapas and drinking wine then you will eventually start to enjoy that flavour.

If you repeatedly expose yourself to certain aromas and tastes then you start to recognise them more easily.

That is all someone who is described as having a sophisticated palate has done, they have taught themselves how to taste and identify flavours by repeated exposure.

This is done in many ways and there have been experiments to show why this is the case and how it can be explained.

There was an MRI experiment with wine held in Italy. A number of sommeliers were placed into an MRI machine and their brains were scanned whilst being fed wine through a straw (not the desired way to drink wine but when needs must).

Next to them was a group of people who drank wine but were not trained or professionals in any way.

The differences were fairly impressive, the non-professional's brains looked as they normally would with normal activity.

Whereas the Sommelier's brains seemed to light up.

This was in areas of the brain related to memory and abstract reasoning, now it is not because the sommeliers are more intelligent or have better taste buds.

The scan showed that whilst tasting the wine because they had trained themselves, they started to analyse and evaluate the wine, which caused their brains to search out other information.

They tried to identify the grapes so by the flavours they could taste they tried to work out what variety it was - this meant they were remembering flavours they had tried before and trying to evaluate and deduce where the wines came from to work out what the grape was.

This is what makes sommeliers better tasters.

They have studied for years to build a frame of reference for the wines that they have tried, they have a common language or lexicon that they use when thinking about the flavours of wine all of which helps them to boost their ability to discriminate between certain odours

So, by building this frame of reference they are essentially creating a classification system which means they are engaging more parts of their brain in order to understand what they are tasting.

If you think about the first time you tried to learn a language, you didn't do it by trying to learn how to hear better.

You memorise grammar rules, vocabulary, and syntax and you practice the language.

Lather, rinse, repeat.

You do this over and over again until it becomes second nature.

It's a tough notion that in order to become better at tasting wine you need to taste more wine, more regularly.

Some people will think that this isn't for them, that they don't have a good sense of taste or smell but Taste and Aroma Receptors constantly regenerate over time and are replaced.

This means that everyone can be trained to be a better taster.

Now obviously I have a sinister ulterior motive for writing all about how our senses work as this allows me to advertise or plug my WSET Classes.

WSET has been going for 50 years and there are courses all over the world so I highly recommend them to you.

By learning more about the wines as well as tasting them you are building up the same frame of reference as sommeliers have so you will be able to identify more flavours and ultimately enjoy the wine more.

One last point

Know thyself: Personal preference is key.

I personally don’t like sweetness, I’m very sensitive to it so what is sweet to most people is unbearably sweet to me.

This means sweet wines are not to my taste.

I like wines with high acidity, complexity and lots of flavour, not necessarily big bold wines, subtle flavour is fantastic too.

So, I personally prefer Riesling, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay alongside a myriad selection of other wines.

So White Zinfandel, one of the most popular wines in the world tastes terrible to me.

White Zinfandel is a sweet, simple wine with low acidity.

So of course, I don't like it - it is simply put, not to my tastes.

However, this doesn’t mean that White Zinfandel is a bad wine.

It’s not complex, it is sweet and has low acidity, and is not to my taste.

But it's designed that way, most people like wine that is simple, look how popular Pinot Grigio is. Another wine that is designed to be simple.

Most people like sweetness, think of Coca Cola or Pepsi (not getting involved in that one) and how popular they are.

Most people in the world start off liking wines that are sweet, as we are predisposed to like sweetness.

Our palettes change over time, they don't need to but they generally do

So, if you like White Zinfandel and someone tells you that you haven't got a sophisticated palate, then they are dead wrong.

If they are a sommelier in a restaurant then they are terrible at their jobs.

They should be there to make you feel more welcome and to help you enjoy your experience and if they don't have a White Zinfandel then there are a number of wines, they could recommend instead to help you enjoy yourself.

An off-dry German Riesling from Mosel, a Torrontes from Argentina, A Vouvray from the Loire Valley. All of these wines have a degree of sweetness, low acidity but can be complex and interesting.

It is always good to be introduced to something new and the easiest way to do this is to link it to something you already like.

So, don't be put off wine if someone has said something to you in the past.

Just think back and realise they are bad at their job and have vastly different preferences to you.

And if that doesn’t make you feel better there have been numerous experiments done on sommeliers that show they are as human as the next person.

https://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2014/08/the_most_infamous_study_on_wine_tasting.html

http://sciencesnopes.blogspot.com/2013/05/about-that-wine-experiment.html

(Here is a slightly less sensational version of the same experiment)

Enjoy.

And if you think that couldn’t work, I have done this test numerous times in tastings and people always have the same reaction.

Try it yourself – all you need is a room temperature white wine and an odourless red food dye.

We don't go into this much detail during our wine courses but I can always be convinced to go off on tangents.